[

] 17

further spreading the virus. The violence against women in

the Zulu culture is the result of a lack of education, fuelled

by the spread of misinformation in the population perpetu-

ating the notion of submissive women and dominant men.

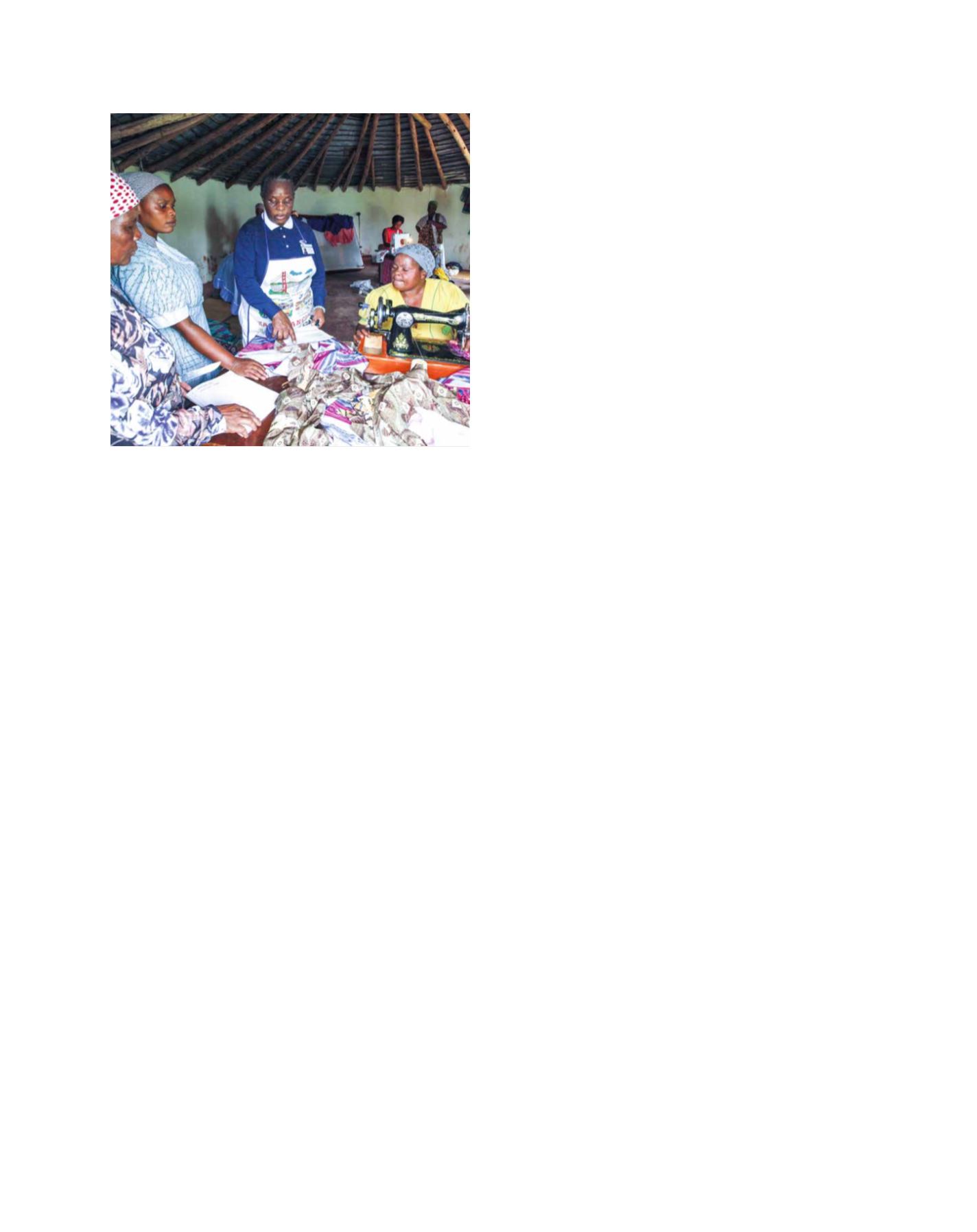

Tzu Chi’s long-term humanitarian project first began in

1995 in South Africa, with the mission of providing health

care for those suffering from HIV and AIDS and stopping

the spread of the deadly disease through education. Upon

witnessing the intimate care provided for the AIDS patients,

several of the Zulu locals in the Durban region no longer

feared the spread of the disease through touch, and ceased

to alienate their ailing brethren. Many of the Zulu women

became volunteer caretakers under the Tzu Chi name, and

the AIDS patients cared for by the volunteers retained their

humanity until the bitter end. The organization’s volunteers

that emigrated to South Africa were committed to empower-

ing the Zulu women, spearheading sustainable humanitarian

programmes such as sewing groups that would later develop

into sewing and other vocational skills training centres, as well

as vegetarian farms, all of which are by women for women.

These endeavours are an encapsulation of what is now Goal

5 of the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),

to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.

The vocational training programmes have been crucial for

the betterment of the livelihood of the participating women,

challenging the Zulus’ traditional gender roles of the male

provider and the female caretaker.

Since 1995 more than 800 local community members,

most of them being Zulu women and girls, have become

Tzu Chi volunteers carrying out missions of compassion and

humanistic aid projects to those less fortunate; missions and

projects all led and operated by local women in the commu-

nity, many of whom were indigent and previously in need

of aid themselves. These Zulu women, who now don the

blue and white uniform worn by Tzu Chi volunteers world-

wide, have established more than 500 vocational training

centres in various communities, teaching more than 12,000

women how to sew and make other handicrafts and, further,

to sell their created products, generating a liveable income

for themselves and their families.

The growth in capacity, quantity and quality of this

programme is a testament to Cheng Yen’s vision of women’s

empowerment, and a testament to how effective humani-

tarian projects actually are if they place the agency of the

community first. As stated, although the provision of aid is

important, it can only be the first initial, if not the last, step

to humanitarian projects; and Tzu Chi’s Zulu volunteers are

learning this as well. In addition to empowering themselves

and other women in South Africa, these volunteers have,

since 2012, begun to implement humanitarian projects to

help communities and individuals in neighbouring coun-

tries. The volunteers that plan, coordinate and carry out

missions of charity and compassion know full well the situ-

ation of those they are giving aid to, understanding their

plights and often sharing the same pain and struggles,

giving them the knowledge and will to enact humanitarian

missions. This encapsulates and distinguishes Tzu Chi’s

relief programmes and mission of charity: the empower-

ment of those that already do not have much to lead, take

control of their lives, and then give back to those even less

fortunate, thereby encouraging those who have been given

aid to give back and, perhaps one day, become Tzu Chi

volunteers themselves.

Another reflection of the success of the programmes in

South Africa is the display of courage among its own contin-

gent of Zulu volunteers. In response to the surge of rape and

violence against women in Zulu culture, the native volunteers

found the courage to form an anti-rape group, provid-

ing psychosocial support to victims of sexual violence and

encouraging legal action against their oppressors. Through

the realization of their own inherent power, they were able

to find the courage to face some of the darkest and cruellest

aspects of humanity, which had affected many of them on a

deep personal level.

It is in this situation that the meaning of empowerment, at

least to that of Cheng Yen and Tzu Chi, can be revealed. It is

not a single thing to be given, just as courage cannot be given

or provided; rather, it is a mindset, or even a state of being,

that is realized internally. Through the operational perspective

of empowering women by way of programme projects, it is

important for humanitarian actors to remember that dignity,

agency and power are not things or material possessions that

can be given, but rather inherent and universal human rights

to be realized.

In line with the Paris agreement and climate action (SDG

13), the Venerable Dharma Master Cheng Yen initiated a

global movement to combat the nature of large agribusiness

and the effects of factory farming on the changing climate,

all of which contribute to roughly 17 per cent of anthro-

pomorphic greenhouse gases. Termed Ethical Eating Day,

participants of this global movement, such as the female

Zulu volunteers in South Africa, commit to a day of meat-

less meals on 11 January, empowering them to take action

through conscious eating habits in the household and

helping to create a better world.

Zulu women are taught employable sewing skills, challenging the traditional

gender roles of Zulu culture

Image: Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation

G

ender

E

quality

and

W

omen

’

s

E

mpowerment