Positive change

While it is too early to determine the sustainable impact

of the CC programme, early indicators are positive. Thus

far, the pilot programmes in both South Sudan and Somalia

have trained over 600 service providers, worked with over

1,000 community discussion participants, engaged 50,000

people in collective community actions and community

events, and reached over 17,000 through radio-based

awareness-raising efforts.

Emerging evidence also shows that community discussion

dialogues promote community action and contribute to safer,

more peaceful communities. Trained Community Discussion

Leaders demonstrate increased awareness and understanding

of the negative impacts GBV can have on community cohe-

sion. Service providers across many sectors also demonstrate

greater understanding of the specific needs of survivors, as

well as the positive impact they can make, including as role

models in their communities.

Preliminary findings point to significant differences in

outcomes between control and intervention groups, with

the latter reporting a reduction in acceptability of the social

norm of ‘protecting family honour’, as well as the norm of

blaming a woman/girl for the sexual violence she has expe-

rienced. Intervention communities also report a reduction in

intimate partner violence and the acceptability of husbands

using violence against their wives.

In the CC programme, communities are the engine of

transforming lives and preventing violence against girls and

women. They are also the voice to advocate for systems

change and accountability to better prevent and respond

to violence.

We hope this example inspires and translates across the

globe as we collectively aim to achieve the Sustainable

Development Goal 5 target of eliminating all forms of violence

against all women and girls in the public and private spheres.

• Conduct trainings for teachers and non-teaching staff to

understand and sign the code of conduct.

• Implement a zero-tolerance policy on sexual exploitation

and abuse.

• Incorporate life skills into school curricula to promote

self-esteem and confidence among students, especially

girls, and to challenge negative social norms.

While monitoring is ongoing, at the time of writing, three

schools were visited and all of them had implemented at least

one of the recommendations.

Improving the justice system

Prior to the CC programme trainings, some members of

customary courts were unaware that sexual violence is a crim-

inal offence under the Penal Code and did not know that only

formal justice systems can handle such cases. Police officers

were under the incorrect impression that certain paperwork

and reporting was a precondition to survivors being able to

access medical care.

The training helped participants understand these basic

laws and policies as well as their roles in preventing and

responding to sexual violence. In one community, as in the

one mentioned above, a clear legal response protocol was

developed by participants, highlighting do’s and don’ts for

both customary and formal legal structures to support survi-

vors seeking legal redress.

In another location, a mentoring and supervision plan was

developed after the training, and follow-up meetings are ongoing

among participants and the county police inspector to discuss

the role of law enforcement and the courts in providing justice

to women and girls who have experienced sexual violence. The

CC programme training module for law enforcement actors was

also shared with the South Sudan National Police Services as

potential input to the national police training curriculum.

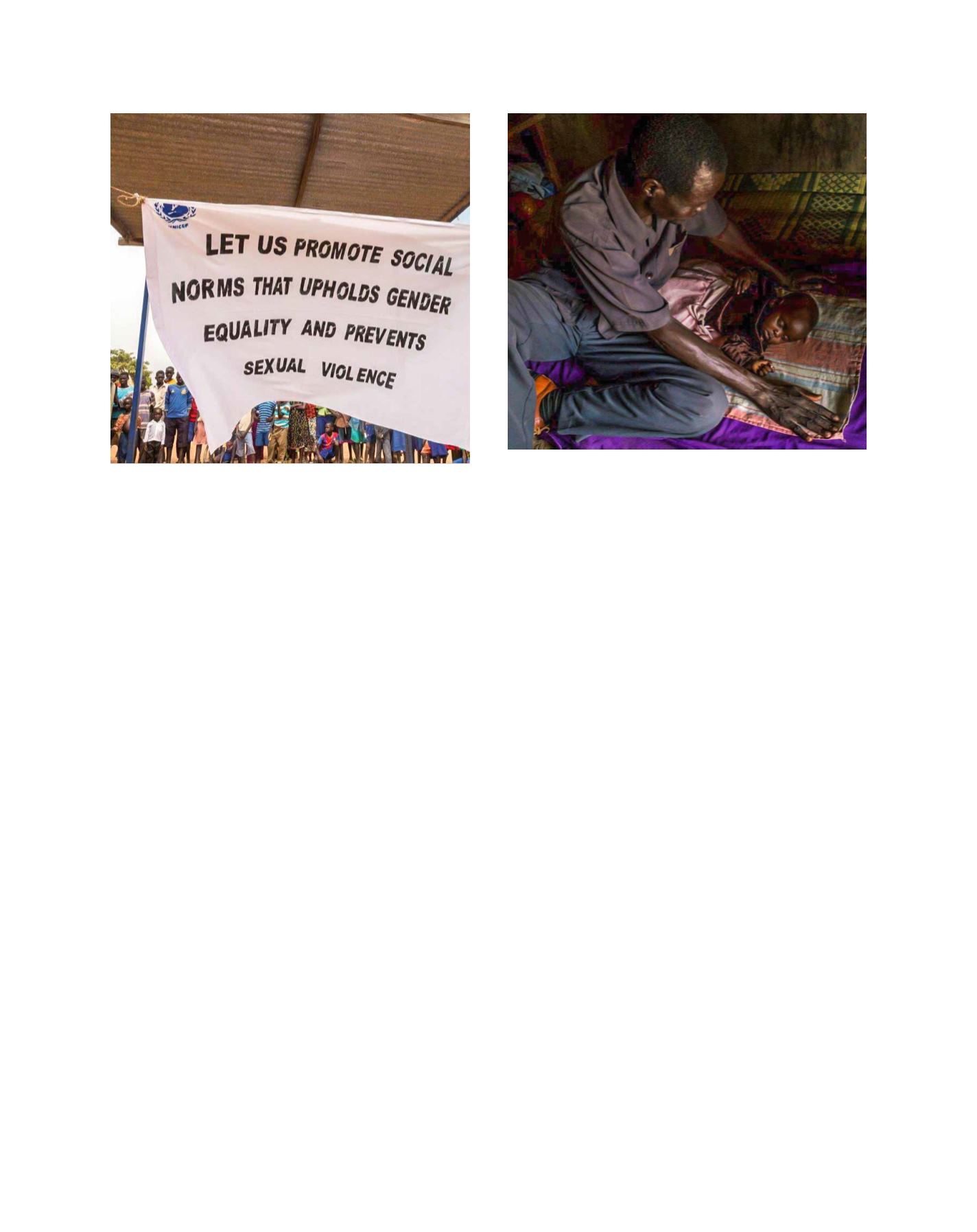

Mayen Awak, Senior Community Engagement Officer for the Organization

for Children’s Harmony in Gogrial, worked closely with community members

to bring the CC programme to completion

Image: UNICEF/Adriane Ohanesian 2015

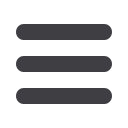

Children gather for the launch of the CC programme in Gogrial West, South

Sudan on 16 November 2015

Image: UNICEF/Adriane Ohanesian 2015

A B

etter

W

orld

[

] 42