[

] 72

village community banks. Regionally, there is a need to

provide disaggregated data for effective decision-making,

service delivery and citizen engagement; and information

for Africa to own its narrative.

3

There is also a need for

continued research and initiatives targeted at the ASM

subsector, to define clear policy guidelines in relation to

data collection, development planning and transforming

the sector into decent employment for women.

Not surprisingly, the multifaceted nature of livelihoods

strategies for women who work in ASM also emerged as

a key theme. For many women, involvement in ASM is

part of their livelihoods strategy and is balanced with other

income-generation activities such as agriculture, as ASM is

often seasonal.

Regarding collaboration between LSM and ASM, common

themes were conflict over allocated mining concessions;

women in ASM feeling disempowered in their relationships

with LSM; lack of government support for LSM-ASM collabo-

ration; lack of incentives for LSM engagement with ASM; and

the potential for other agents (such as the Ghana University of

Mines and Technology) to broker positive capacity-building

opportunities between LSM and ASM.

A recurrent theme in all the workshops was the need for

women to organize better. Naila Kabeer and others, writing

on ‘organizing women in the informal economy’, quotes

from Shalini Sinha that “studies on women have suggested

that fear cripples women to effectively organize to receive

common resources for their collective good.”

4

Women have

been brought up in fear of their husbands, employers and

communities. They live in constant fear of losing their liveli-

hoods, starvation, losing their children to illness and being

thrown out of their homes. However, ECA’s research on

women in ASM alluded to another dimension or constraint to

organizing: opportunism has led to a scramble for resources

by the apex women’s mining organizations at the expense of

rural women. Most of the ASM groups were organized only

on paper and at the executive level, with no outreach activi-

ties for women at grass-roots level.

Women miners’ associations and women’s cooperatives are

an area of potential opportunity for capacity development and

provision of improved services to members. Governments,

development partners and financial institutions often find it

easier to engage with and provide support to groups rather

than individuals.

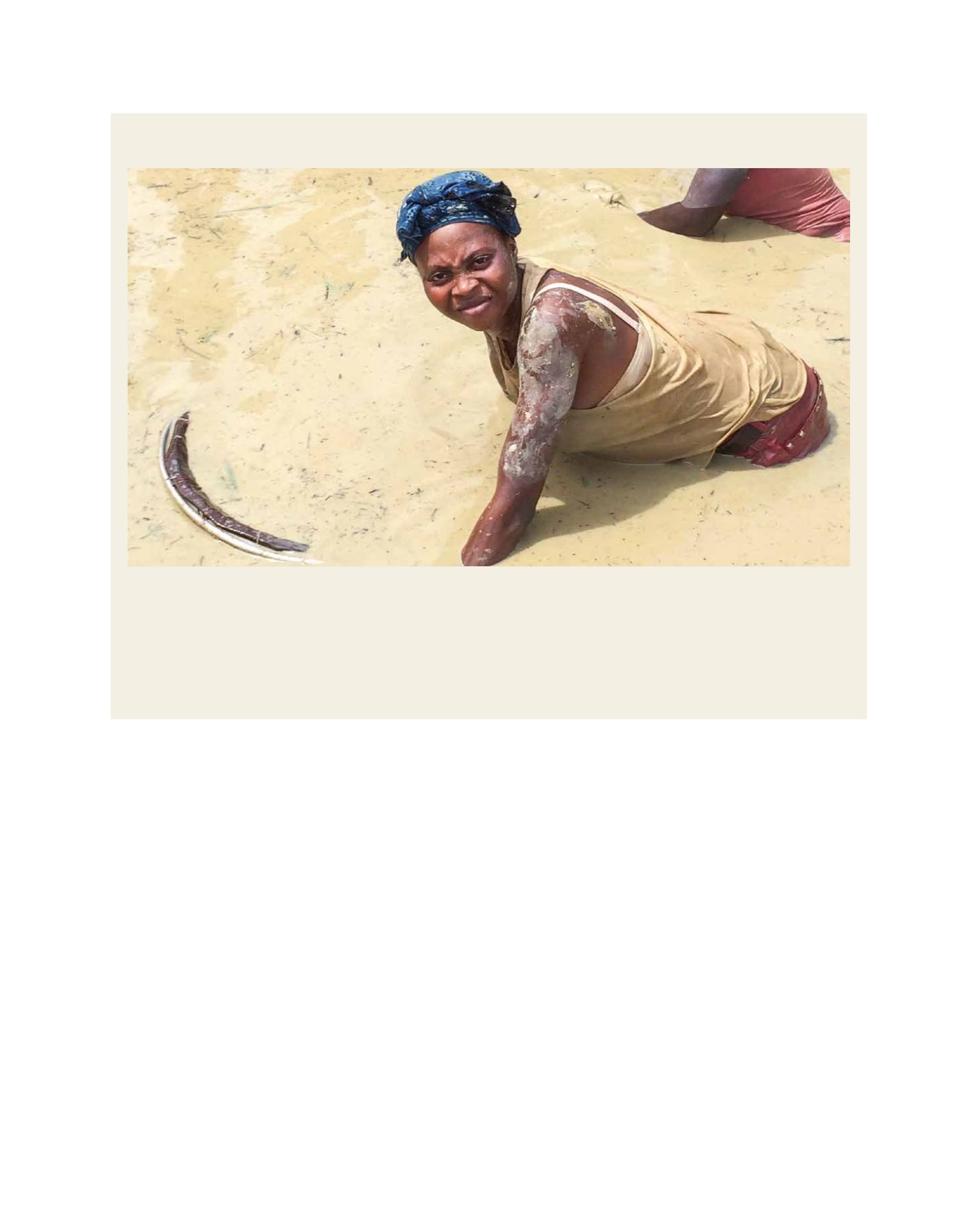

Profile: Rebecca

Rebecca is a 21-year-old galamsey miner at Kwabeng. Galamsey – an

adulteration of the phrase ‘gather them and sell’ – is a form of mining

in the informal sector and is outside the legal and regulatory framework

of the country. The operations may be mechanized or artisanal, but the

miners do not have legal access to the mineral concession.

Rebecca is educated to secondary school level, but has not

undergone any technical training. She has a six-month-old baby, and

came to the mining site on her own to make a living. “Life became

difficult for me after delivering my baby, as the baby’s father abandoned

us, leaving us with no financial support, so I started doing galamsey

work to make ends meet,” she says. “My family members think the

galamsey work is difficult but they cannot take care of me either so

they do not say anything when I am out here working. I use the money I

make to take care of my baby and myself. I am better now than before.”

Rebecca works in galamsey mining to make a living

Image: ECA

A B

etter

W

orld