[

] 24

Comprehensive and tailored approaches

for women’s economic empowerment

Leena Akatama, Senior Adviser – Gender, Department of Development Policy, Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland

W

omen’s share of the global workforce has

increased more or less at the same speed as

international trade, and is estimated at around

40 per cent. For many women, jobs are their gateways to

the formal economy, their own income and, subsequently,

independence, also affecting their power relationships in

the household.

However, these are only the first steps towards a more

profound equality. The majority of women in developing

countries still work in the informal economy with limited

access to occupational safety, services or social protection.

Furthermore, women are still primarily responsible for unpaid

care work, are left with little or no time for recreation and

rest, and are predominantly considered as secondary earners.

The gender gap in education limits women’s ability to grasp

new work opportunities, although the gap in basic education

is gradually closing. Vocational training more often benefits

men than women, because of social norms and the perceived

limitations of women’s command of their own time or their

safety. Women in many developing countries have weaker

rights to own land or other property, hindering their capabili-

ties to invest or acquire productive resources such as finance.

Also, limited access to sexual and reproductive health

services and unrecognized rights to make decisions concern-

ing one’s own life weaken women’s potential to participate in

the economy. Many are juggling with poor health outcomes,

increased care work, financial consequences of increased

family size, and often the risk of violence.

According to a recent report by the Overseas Development

Institute (ODI), women’s economic empowerment is a process

where the capacities of individuals, participation in decision-

making, access to and control over resources, and participation

in collective actionmerge. Therefore, be it freedom from violence

or harmful practices, access to sexual and reproductive health

services or access to information and communication technolo-

gies, all the targets of United Nations Sustainable Development

Goal (SDG) 5 contribute to women’s economic participation.

The study points out six direct factors that either enable

or hinder women’s economic empowerment: education and

skills development; access to quality, decent work; unpaid

care work; access to economic resources; collective action

and leadership; and social protection. These are accompanied

by underlying factors, namely labour market characteris-

tics, fiscal policy, legal and policy framework, and gender

discrimination. Discrimination is prevalent in all 10 factors

and manifests in various ways.

Female workers with relatively low educational levels

are particularly vulnerable in situations where competitive

advantage is sought through low salaries and flexible working

conditions, while women’s status is strongly defined by tradi-

tional gender roles. They are more affected by the gender

role gap than those men and women who have been able to

take advantage of trade openness, technological change and

the widespread availability of information. Furthermore,

inadequate or unavailable social protection makes women

particularly vulnerable to shocks such as occupational hazards,

loss of employment, economic crisis or drought. To date, many

economic advances for women have been made within the

existing structures and power relations, without challenging

them. Addressing the discriminatory perceptions that form and

inform institutions, policies and legal frameworks remains a big

task and requires consistent gender mainstreaming.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Agenda

2030) is the new platform for development policy and a great

opportunity to promote gender equality. It is both a stand-

alone goal and a cross-cutting objective in the SDGs, reflected

in many targets and indicators across the agenda. This

comprehensive approach is useful to see the interlinkages

between the goals but it also poses a challenge of complexity

for effective implementation and monitoring.

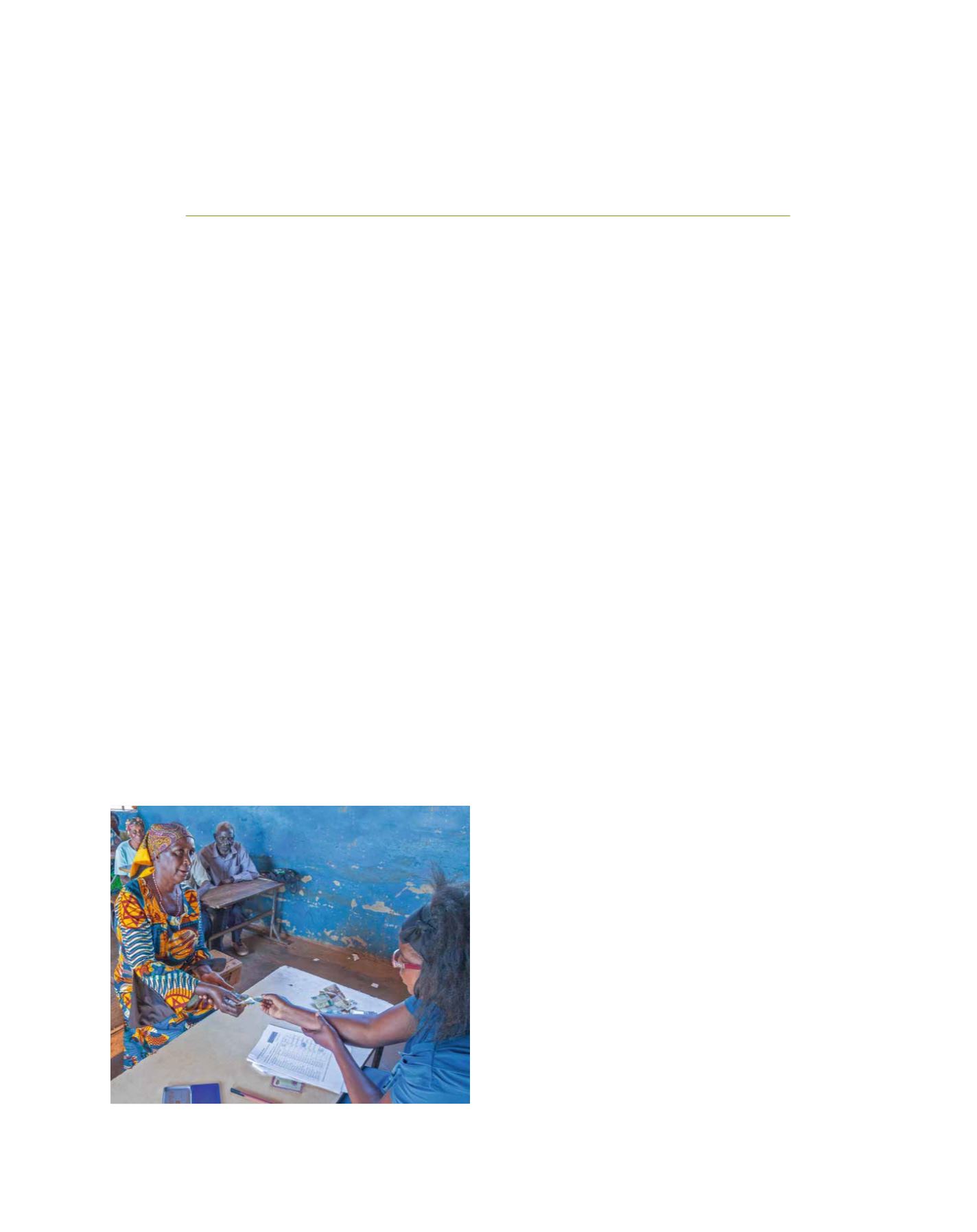

Image: Unicef Zambia

An SCT beneficiary recieving a payment at the Mukuni paypoint in Zambia’s

Kazungula district

A B

etter

W

orld