[

] 26

ity is a way forward to implementing desired macroeconomic

policies. Poverty reduction is not possible without addressing

gender equality questions.

One example of our support to women’s economic empow-

erment is Women’s World Banking (WWB). According to

recent studies by WWB, financial institutions often do not

know their potential customers, and financial services meant

for women often fail because they are not designed for women’s

needs. WWB works with financial institutions to increase low-

income women’s access to financial tools and resources and

to invest in women as customers and leaders. WWB assists

financial institutions with in-depth market research, finan-

cial product development and consumer education. For the

institutions, this is a great way to increase their customer base

by serving those that were previously left unserved by their

regular financial products.

For instance in Jordan, WWB’s network member has devel-

oped the country’s first private health microinsurance, which

provides benefits after hospitalization that clients can use for

transportation to hospital or to cover lost business revenue.

The product is widely used by women to cover maternity-

related hospitalization costs. It has 105,000 active policies and

has been expanded to Peru, Uganda, Morocco and Egypt.

Another example is savings schemes. Women whose earn-

ings are low and unpredictable are able to save on average

10-15 per cent of their income, but they often lack reli-

able savings schemes. For financial institutions, savings

schemes are easier to manage than credit as they do not rely

on in-depth understanding of the market dynamics. They

also provide opportunities to market other financial prod-

ucts to savings clients. WWB network members in Pakistan,

Colombia, Kenya, the Dominican Republic, Nigeria, Malawi

and Tanzania are offering savings schemes that operate in the

markets where traders, most of them women, work, giving

them convenience and security.

The savings schemes currently have 1 million active

accounts. Notably, financial products designed for women

often end up enhancing the financial inclusion of men, and

thus reducing inequality overall. Approximately 1.6 million

clients currently benefit from the financial products of WWB

network members, including credit, small to medium enter-

prise services and mobile financial services.

Another encouraging example of women’s economic empow-

erment and ‘leaving no one behind’ is the Social Cash Transfer

(SCT) programme in Zambia. Despite Zambia being considered

as a low-middle income country, 60 per cent of its population

lives in poverty and 42 per cent in extreme poverty.

SCT started as a one-district pilot and has grown into a

nationwide programme with significant government financing.

In 2016, it was scaled to 78 districts, covering approximately 8

per cent of the population. SCT’s success is due to years spent

designing a targeting system that best reaches the poorest

Zambians, consistent impact assessment during the implemen-

tation, and evidence-based advocacy for government financing.

The basic idea of SCT is to provide reliable cash transfers to

poor families who are either destitute or incapacitated. Although

the benefit is designed to assist the entire family, women are

often the recipients. Widow or elderly headed households with

orphans, households with an elderly member or a member with

a severe disability are targeted. All beneficiary households are

assessed based on their welfare and incapacity status, and the

targeting is done in cooperation with the community and the

district welfare officer. The payments are handled by government

teachers or health workers, reducing the transaction costs.

The transfer amount is relatively small, ZMK 70 or just over

US$7 per month. SCT is an effective and inexpensive poverty

reduction programme which the Zambian Government will

gradually upscale and cover the costs of the transfers. Impact

evaluation has shown that SCT is more successful than tradi-

tional poverty reduction programmes such as material welfare

support and farmer input support programmes.

For every Kwacha transferred an additional 0.68 Kwacha

has been generated through productive impacts. This means

that SCT beneficiary households have invested in agricul-

ture production, livestock rearing or non-farm enterprises

and thus, the depth of poverty has reduced. Families have

increased food consumption with 95 per cent of households

eating more than one meal a day. Harmful consumption such

as tobacco or alcohol has not increased. There were significant

improvements in living conditions as more families acquired

mosquito nets, their own latrines, lighting and cement floors.

The overall welfare of children has improved, incidences of

diarrhoea have reduced, more children have their material

needs met (two sets of clothing, shoes and a blanket) and

more children aged 15-17 are in school. Beneficiary testimo-

nies have also consistently voiced that SCT has helped ensure

families’ dignity as they are no longer dependent on other

people and therefore have the confidence to participate in the

community and prepare for future shocks.

Women’s economic empowerment requires both comprehen-

sive and tailored approaches and interventions to succeed. The

big challenge that affects women’s participation in the economy

at large is gender discrimination and it is important that we

address the discriminatory social norms, attitudes and practices

as we provide other kinds of support. Considering the potential

women possess for the economy and the well-being of society,

we cannot afford to miss this opportunity to tap it.

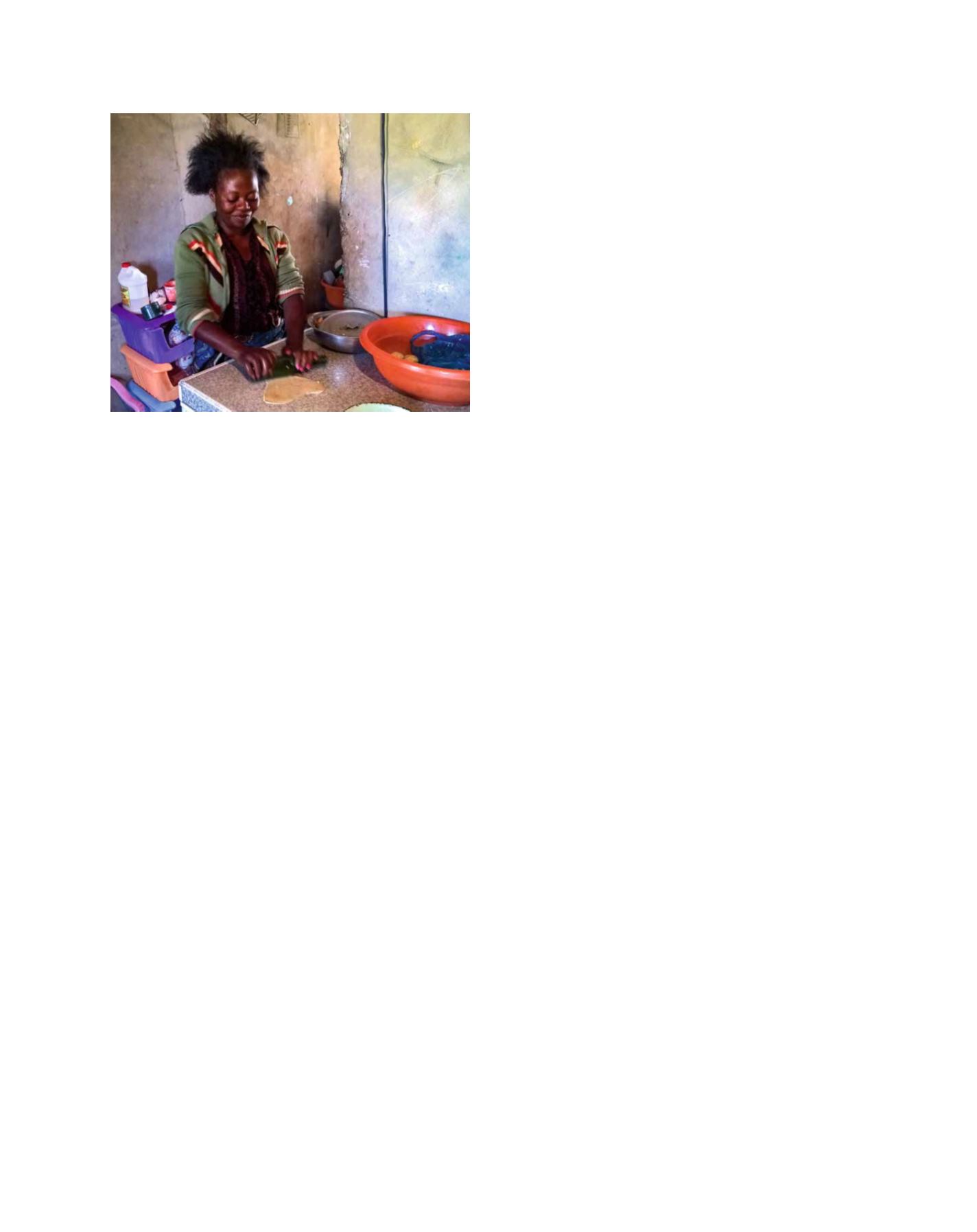

Image: Timo Olkkonen

Supported by SCT, this woman, whose husband has a disability, has started a

baking business to earn income

A B

etter

W

orld