[

] 29

Women’s education is an extraordinary asset that remains

largely unused. If low income countries achieve the target of

universal secondary education by 2030, per capita incomes

will increase by 75 per cent. It is reported that in develop-

ing countries, women invest 90 per cent of their income

in the well-being, education and nutrition of their families

(compared to about 35 per cent for men).

Literate societies where women and men, girls and boys

benefit from decent education systems and lifelong learning

and development opportunities are more likely to be able to

reduce poverty, live healthier lives and acquire better employ-

ment prospects. According to the 2016 Global Education

Monitoring (GEM) Report,

1

educated mothers will save the

lives of their children – 3.5 million child deaths could be

prevented from 2040-2050 in sub-Saharan Africa alone by

achieving the 2030 education commitments.

The GEM Report notes that there are 758 million illiterate

adults in the world and two thirds of these are women like

Rokhaya. The sad part is that this proportion has remained

unchanged in the last 20 years. In Senegal, women accounted

for close to 2.5 million of the illiterate population in 2015,

according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics – double

the proportion of men.

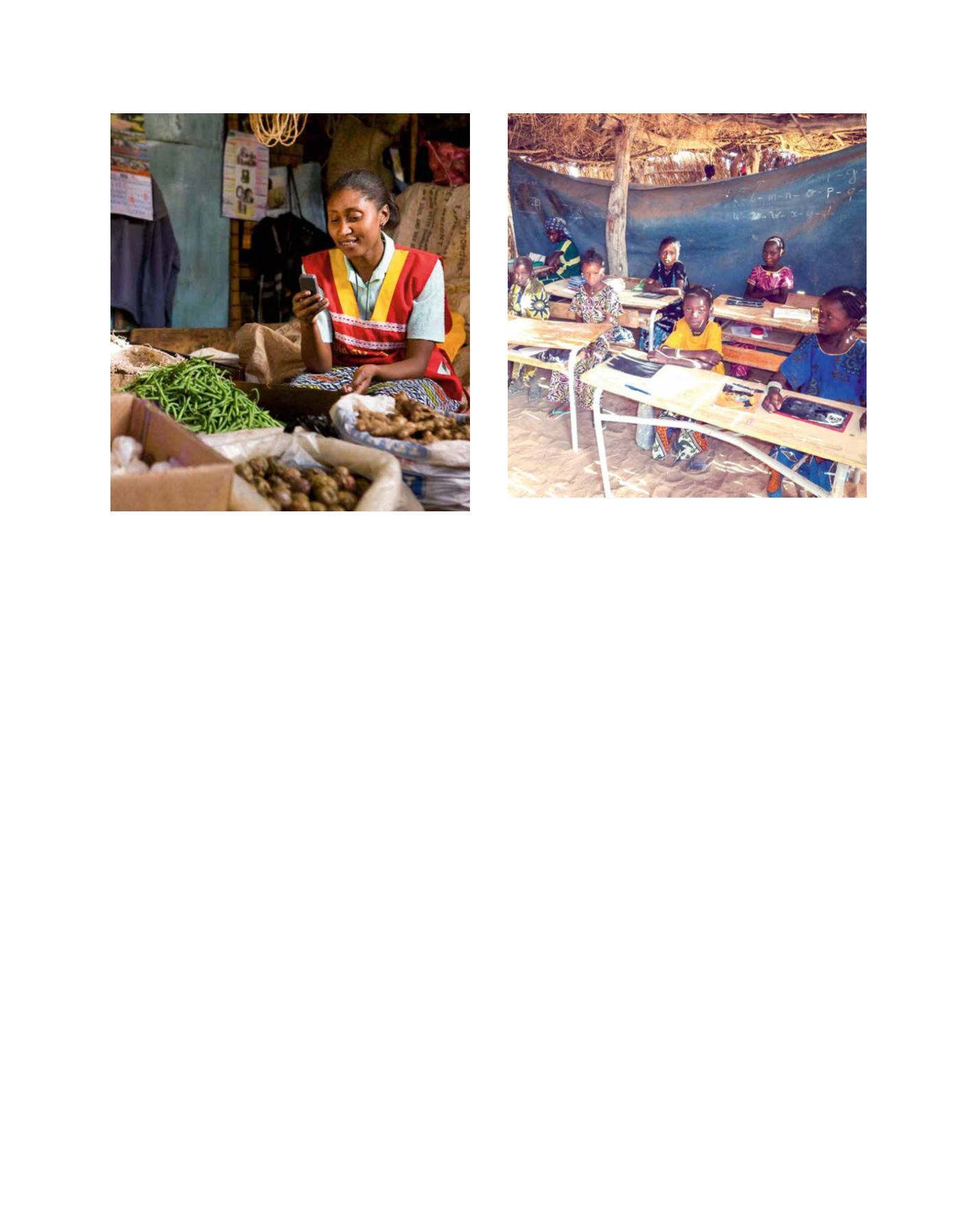

The GEM report finds that 15 million girls of primary-

school age will never get the chance to read or write in a

primary school setting. These girls are not expected to ever

set foot in a classroom. If this continues, the most disad-

vantaged girls in sub-Saharan Africa for instance, will only

make it to school in the year 2086. Education can provide

girls and women with the knowledge and skills they need

to fulfil their aspirations. Or in some cases, simply to free

themselves from a vicious cycle of continued dependence

or poverty.

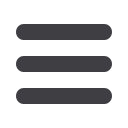

In that context, mobile phones represent a unique

opportunity.

Mobile phones can reach the unreachable and they can

motivate them to learn new skills in their own time and

beyond the institutionalized school system. For instance, in

Senegal, mobile phone subscriptions skyrocketed in recent

years: according to the World Bank, they went from 1.1

million in 2004 to 14.4 million subscribers in 2014.

Since mobile phones include services that rely on literacy

skills such as text messages, e-mail and for some Internet

access, the device is considered a very useful pedagogical tool.

It provides learners with critical and cognitive skills they can

apply to real-life situations in their context.

Mobile phones open up new ways of communication and

networking within small communities. They could also

lead to new income-generating activities: after she gradu-

ated from UNESCO’s PAJEF programme, Rokhaya realized

that she could use her new skills to make some money for

herself and her family. She began renting her phone and her

newly-acquired writing skills to women who were in the same

situation with their husbands or kids in a different part of

Senegal. Through her phone she met new people, made new

friends and earned additional income.

But more needs to be done in that respect, as there is a clear

digital divide which negatively reinforces the gender divide.

Globally, 37 per cent of women are online (as opposed to 41

per cent of men). In the developing world the gender gap is

much larger. A report by Intel found that “on average across

the developing world, nearly 25 per cent fewer women than

men have access to the Internet, and the gender gap soars to

nearly 45 per cent in regions like sub-Saharan Africa.”

2

This digital divide in not inconsequential: a study in 12 Latin

American and 13 African countries

3

found that the gender

A woman using her mobile phone at the street market

Image: UNESCO/Nokia

Girls attending school in Northern Senegal; education is key to development

here, where about half of the population are illiterate

Image: Birama Touré

G

ender

E

quality

and

W

omen

’

s

E

mpowerment