[

] 60

Bangladesh as well as encouraging savings and creating rural

capital through the formation of SHGs.

In Maldives, women are largely engaged in the production

of Maldives Fish or smoked and dried tuna. Therefore, the

extent of their participation is determined by the availability

of fresh tuna. In recent years, the Government of Maldives

has encouraged the domestic fishing fleet to target both skip-

jack and yellowfin tuna. The Government has also recently

announced the Fisheries and Agriculture Diversification

Programme, under which soft loans (at 6 per cent interest)

will be provided to cooperative societies for value addition

and enhancing productivity.

In Sri Lanka, as in the other countries of the region, women

are mostly involved in fish processing and to a small extent in

marketing. The role of women is more visible in inland fisher-

ies and fish farming. The policy objective of the Government

of Sri Lanka is to ensure sustainable production through

community participation. The legal framework of the country

emphasizes stakeholder consultation – which potentially

engages women in the decision-making processes.

In India, women have played multiple roles in fisheries,

apart from their key role in raising the family. Policy supports

have facilitated improvements in their skills, the formation of

women’s cooperatives and SHGs and access to credit. Besides

their traditional role in post-harvest activities, involvement

is diversifying to areas such as seaweed farming and other

mariculture activities. The new draft Marine Fisheries Policy

of 2016 aims to strengthen the role of women in fisheries.

It proposes that the “Government will … further enhance

support by way of forming women cooperatives; women-

friendly financial support schemes; good working conditions

that would include safety, security and hygiene and transport

facilities for retail marketing; encouragement to take up small-

scale fishing, value addition activities; and also play an active

role in fisheries management.” In addition, it also suggests

that the coastal provinces should consider increasing the area

presently reserved for artisanal fishing. Such an action could

see the revival of the role of women in active fishing as artisa-

nal fishing mainly comprises the marginal section of society

catering to local markets. The policy objective of reduction in

post-harvest losses could help ensure better financial remu-

neration for women engaged in fisheries.

In spite of the multidimensional roles of women in fisher-

ies, their contributions often go unnoticed. There are several

reports of discrimination in wages and working conditions,

especially in the processing sector. Various social indicators

such as sex ratio and literacy rate also suggest that there is

a need to empower women. While these features may be a

reflection of society at large, in the context of fisheries, it

implies that women in practice are far from the decision-

making processes at the macro level.

Experiences so far on the involvement of women in the

marine fisheries sector show that the removal of constraints

can lead to their productive engagement. The first constraint

is that despite women playing a significant role in distribu-

tion and post-harvesting, they do not have much power to

influence the process. The second constraint is that their role

in economic activities is not reflected in their social status

as captured in sex ratio and literacy rate differentials. The

third constraint is that unlike men, examples of successful

women’s enterprises show the necessity of group effort. In

other words, solo ventures by women possibly have little

chance of success. These factors could inhibit unlocking the

full potential of women in enterprise and decision-making.

While these constraints are mostly part of the position of

women in the larger society, the fisheries sector can bring

in changes by moving to principles as described in the FAO

Voluntary Guidelines on Small-scale Fisheries Governance.

Securing women’s role in fisheries

The Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-scale

Fisheries (VG-SSF) is an international effort in securing women’s

role in fisheries.

Rights and duties are the cornerstone of any successful governance

mechanism. The 1995 FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries

(CCRF), which documented best practices in fisheries governance,

arguably focused on this. To further support implementation of the

CCRF, in June 2014, 143 FAO member countries adopted the VG-SSF.

As the title suggests, these guidelines focus on small-scale fisheries,

which constitute about 90 per cent of the global fishery.

The VG-SSF aims at ensuring human rights and dignity, gender

equality and equity, transparency and rule of law, participation,

accountability and social responsibility by empowering small-scale

fishing communities, including both men and women, to participate

in decision-making processes, and to assume responsibilities for

sustainable use of fishery resources. At the same time, the differences

between women and men have been acknowledged and the guidelines

suggest that specific measures should be taken to accelerate de

facto equality. The guidelines call for the state to secure equitable and

appropriate tenure rights to fishery resources (marine and inland) with

special attention paid to women. The guidelines also call for ending all

types of discrimination against women and ensuring secure workplaces

and fair wages while providing them with the necessary support to avail

different resources – such as finance and training.

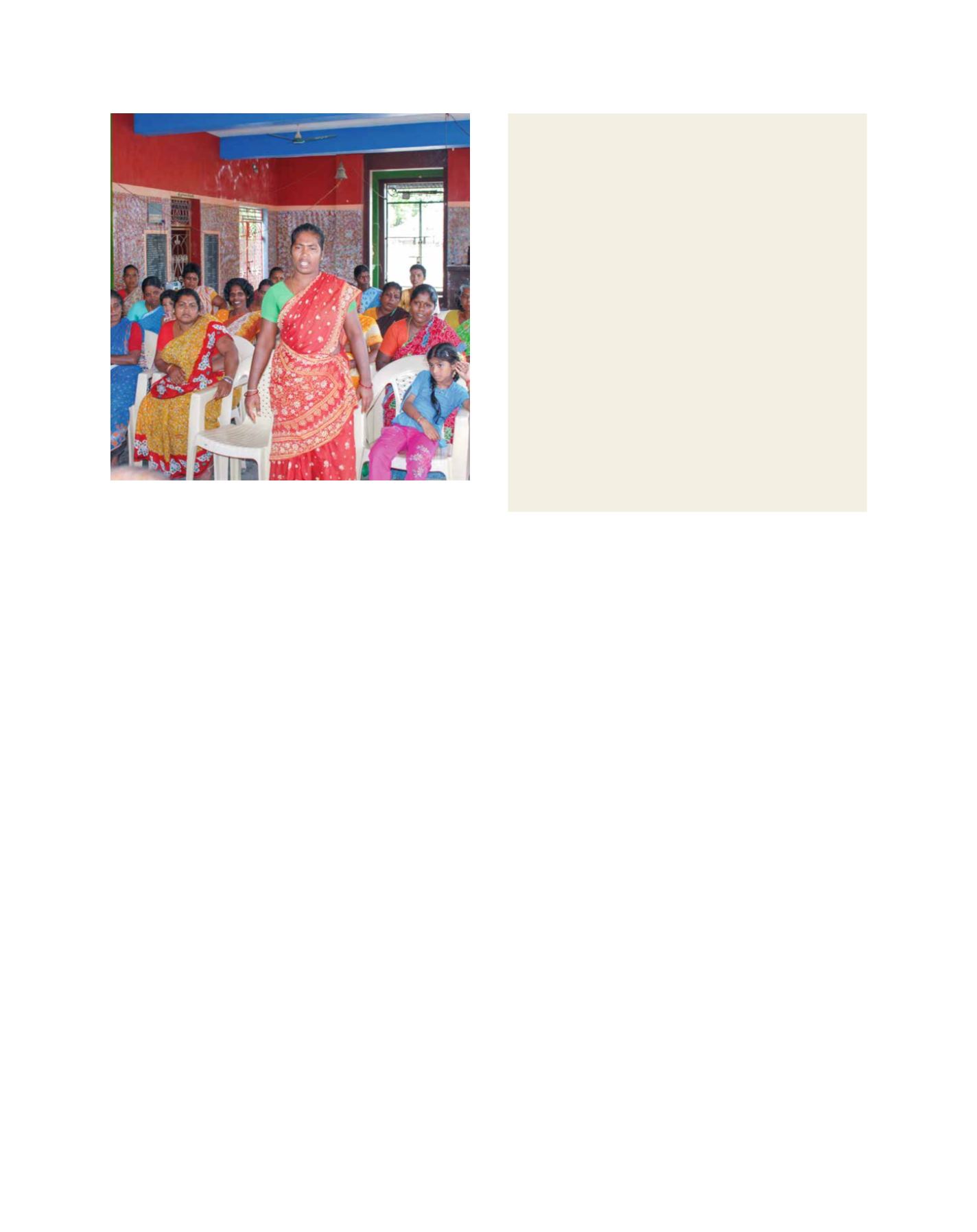

A stakeholder consultation with fisherwomen from Mudasalodai Fish Landing

Centre, Tamil Nadu, India

Image: Y S Yadava

A B

etter

W

orld