[

] 82

productive capacity and sustainable means of income for

the poor. In 2008 IDB and ISFD launched the Integrated

Microfinance Support Program to tackle the lack of access to

working capital within IDB member countries.

In 2010 IDB and ISFD engaged in a partnership with the

Government of Benin to assist the country in achieving its

poverty reduction goals to increase people’s access to microfi-

nance. This programme develops its products on the principles

of participatory Islamic microfinance, which has proven very

popular among the beneficiaries. There is strong demand for

more such products, and Islamic microfinance clearly has a

major role to play in Benin’s fight against poverty.

Benin suffers from high levels of poverty and illiteracy,

problems that leave youth and women with few opportuni-

ties to become economically active. It was ranked 165th out

of 187 countries in the 2015 Human Development Index,

1

but the country is striving to improve its standing through a

range of strategies.

The programme aims to increase employment opportunities,

boost economic activities and reduce poverty for 200,000 people

per year by improving their access to sustainable microfinance

services, market-oriented training and business opportunities.

The Integrated Microfinance Support Program targeted six main

groups: micro and small enterprises including new start-ups;

female heads of households; unemployed youth graduates or

those with professional diplomas; skilled labourers, traders and

craftspeople; deprived rural families; and the active handicapped.

It had six components; three related to programme manage-

ment and the following three, which guided its main activities:

• ‘Revolving microfinance schemes for ultra-poor people

and micro and small enterprises’ provided two lines of

microfinance: small loans for income-generation activities

for groups of ultra-poor people, of which at least 70 per

cent would be women; and larger loans for micro and

small enterprises, economically active poor people and

unemployed youth. Both used Islamic microfinance.

• ‘Capacity-building for microfinance institutions’ entailed

tailored training and support programmes, through

which national and private institutions were to benefit

from training to support the introduction of Islamic

microfinance principles, products and practices.

• The ‘Market-oriented vocational training and awareness

campaigns for ultra-poor people’ component was

undertaken by national partners. It comprised a pro-poor

vocational literacy and awareness programme, and practical

apprenticeship programmes.

The initial aim was that at least 70 per cent of the programme

beneficiaries should be women. But by 2015, 90 per cent of those

who benefited were women – about 150,000 in total. And the

benefits are not just financial; the women describe the pride,

unity, independence and happiness that have changed their lives

for the better since they were able to access working capital to

expand their activities.

One example is the Saint Trinité group. Located in the

heart of Contonou’s poor Yagbé quarter, its 250 members

include widows, disabled people and other very poor women.

Together, they mainly buy fish, which they then smoke or

fry for sale. Their president, Celestine Kounduho, explains

how their lives have changed: “We had never taken any

credit nor had access to markets before. We started with a

CFAF30,000 (US$60) loan. When we repaid this we were able

to borrow more, and now we are working with money from a

CFAF100,000 (US$200) loan. The group is growing and we

can reach out to others. We work and sell together, and now

have the money to buy materials so our children can go to

school, and extra moneys helps us at home.”

The programme’s first phase ended in June 2014, but the

revolving fund that was established continues to fund women’s

groups and small business ventures. By November 2015, around

150,000 ultra-poor women (those earning less than US$1.25 a

day) had benefitted from microfinance, as well as 15,000 men.

The programme has yielded many tangible benefits – and valu-

able experiences to build upon in the future.

IDB believes that an Islamic financial inclusion model can play

a very important role in promoting empowerment and gender

equality. Empowerment, as understood and promoted within the

context of development and poverty reduction, is a multidimen-

sional and interdependent process that encompasses dimensions

of social, economic and political empowerment. The rationale

behind this is that the creation of an enabling environment for

female entrepreneurship will tackle the underlying causes of

women’s and girls’ economic and social exclusion, constraints

of equitable opportunities and participation. This will increase

women’s and girls’ agency and they will have genuine access to

and control over economic resources, participate in the family

and community decision-making processes and have more power

to balance their roles and mobilize against or report violent inci-

dents. This in turn will respond to their strategic gender needs

and enhance their ability to participate in, contribute to and

benefit equitably from development.

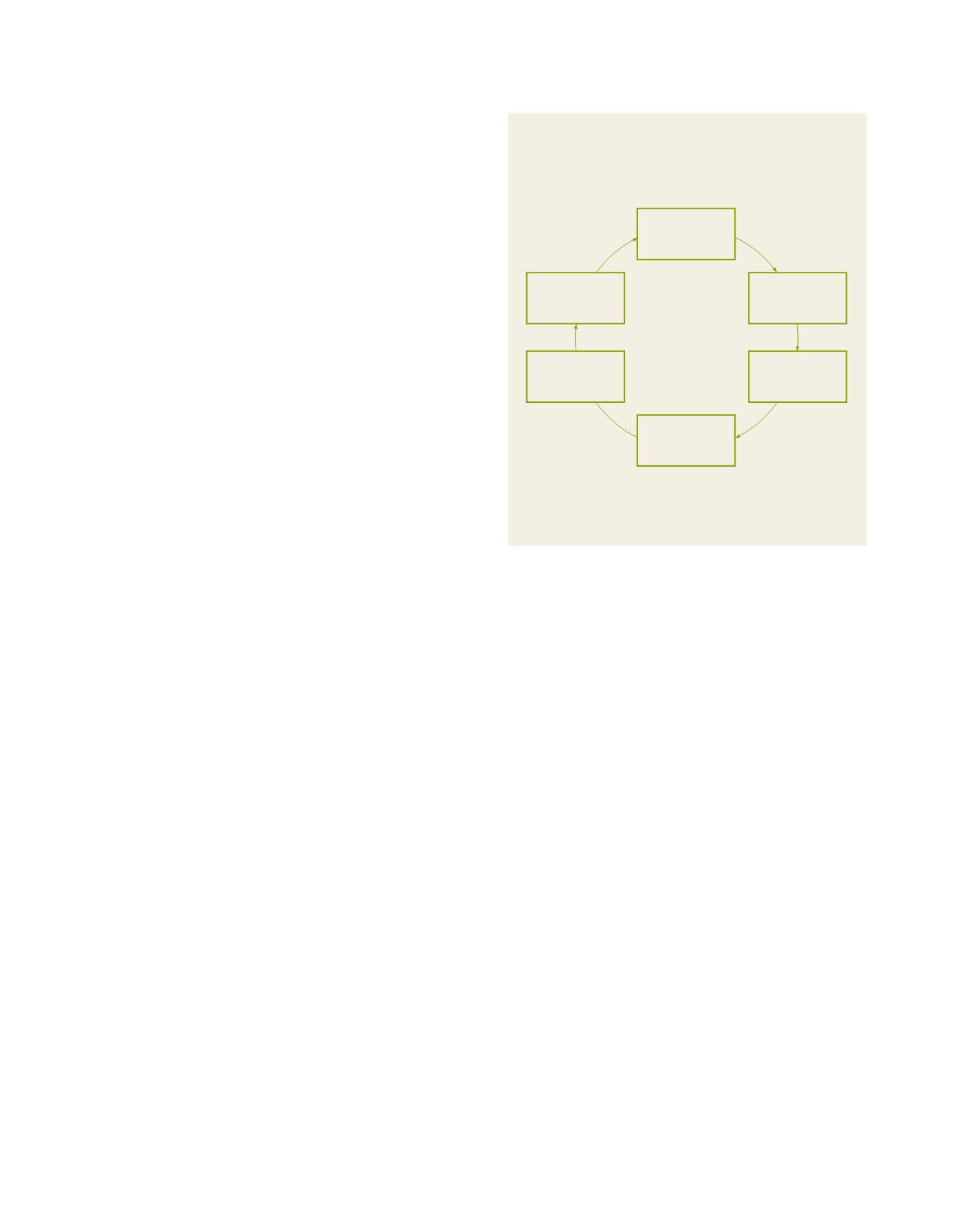

The IDB Islamic Microfinance Facility approach

Viable business

opportunities

Promising

markets

Market orientated

entrepreneurship

skills

Strategic

partnership

Business

development

services and

support investment

Appropriate

participative

financial services

(i) Founding microfinance support on eliminating

main common livelihoods barriers of access to:

(ii) Considering the poor as a business partner not credit consumer

Source: IDB

A B

etter

W

orld