[

] 95

A B

et ter

W

or ld

By 2010, 73 sewage treatment plants with a total capacity of

220 million m

3

/year have been built and 48% of households

were connected to sewage collection networks, but with a

significant difference between municipalities in the rate of

connection ranging from 9.5% to 91%. Operation and main-

tenance was, however, inefficient and in 2010, only nine of

the 73 plants were still operating and the treated wastewater

dropped to 22 million m

3

. Moreover, only four of these nine

plants continued to operate after 2010. Five new plants were

added later to reach an output of 37 million m

3

in 2015.

Similarly, desalination has evolved significantly in the past

few decades, but still faces inherent operational difficulties

that have become more pronounced in recent years.

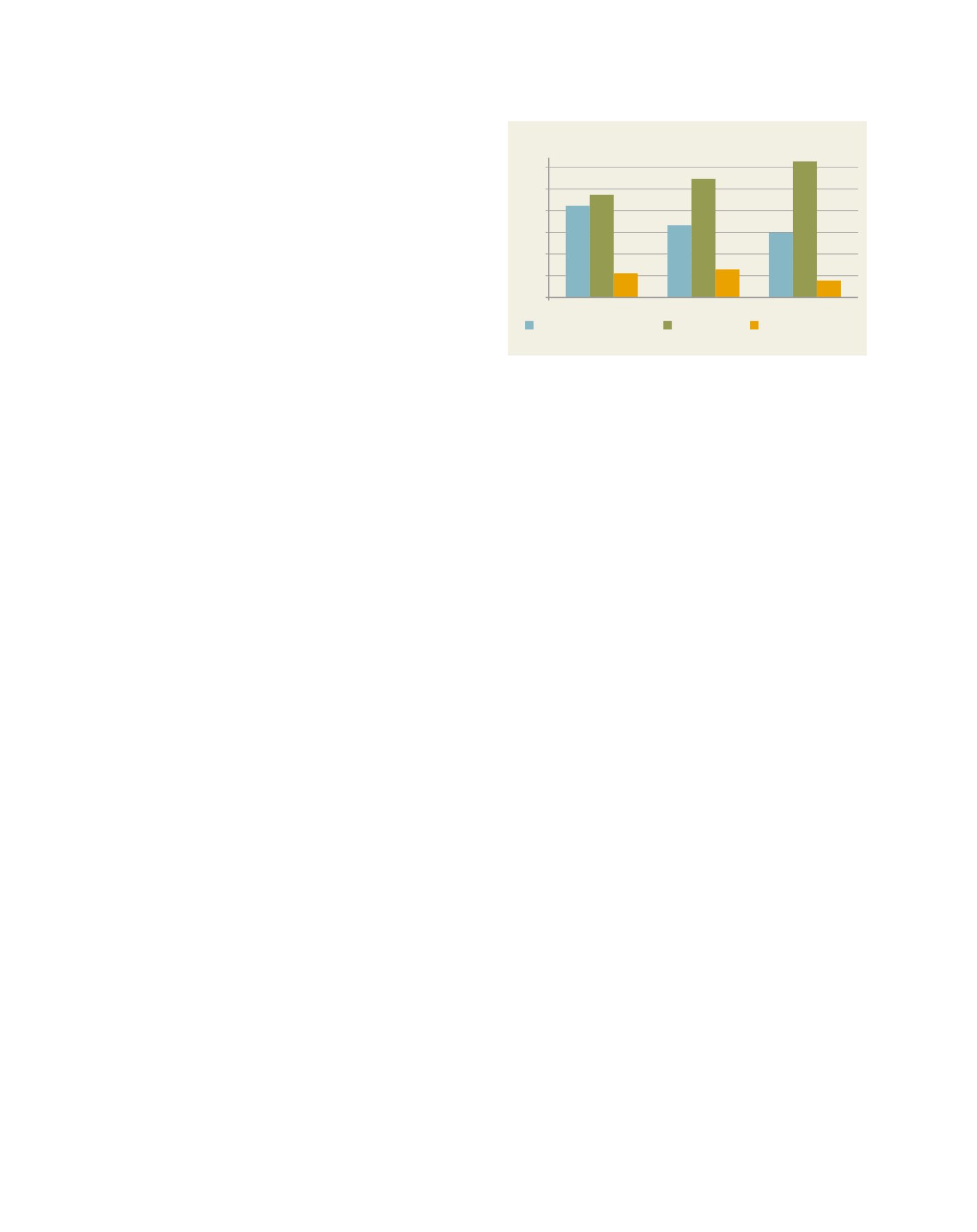

The arrival of the GMR water has markedly reduced the

dependence on local groundwater as a main source of domes-

tic water supply. Accordingly, the contribution of the local

wellfields declined from 42% in 2005 to only 30% in 2015,

while that of the GMR has risen from 47% to 62% for the

same period. This ratio is expected to grow even further in

favour of the GMR.

In 2012, it was reported that 64.5% of the population is

served through public water supply networks, while 17.4%

depends on private wells for water needs and 16% relies

on rainwater collection. The remaining small proportion

relies on other sources such as springs or purchasing truck-

mounted water.

According to the 2014 Africa Water and Sanitation Sector

Report, Libya is among the very few countries in Africa that

met the millennium development goals (MDGs) as the propor-

tion of its population with access to improved water supply

and improved sanitation has reached 92% and 99% respec-

tively in the year 2013, compared to 71% and 84% in 1990.

The MDGs expired at the end of 2015 and are replaced

by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and, in

particular, Goal 6 to “ensure availability and sustainable

management of water and sanitation for all by 2030”. SDG 6

is in line with national water strategies and its implementa-

tion will therefore be of utmost importance in response to

Libya’s international and continental commitments.

Few strategies were adopted in recent years to manage the

water supply and sanitation sector. The National Strategy

for Water Resources (2000–2025) is a comprehensive plan

aiming at reducing the water budget deficit and preventing

further water quality deterioration. It calls for redefining

the priorities of water use; enhancing the contribution of

non-conventional water resources; defining future supply

options, in particular inter-basin water transfer and seawater

desalination; improving water use efficiency; reviewing agri-

cultural policies and practices; investing in capacity building

and institutional reforms; improving legislation and water

pricing; and controlling population growth.

The National Programme for Water and Sanitation was

launched in 2005 for a intermediary period of three years

before finalising water and wastewater plans for all munici-

palities. The programme was centrally managed by the

Ministry of Planning and was later transferred to the newly

formed Housing and Utilities Board in 2006 to be replaced

by the Integrated Utilities Program for the 400 cities and

urban areas of Libya.

In 2007, a Ministry for Electricity, Water and Gas was estab-

lished and immediately embarked on a long-term strategy for

the urban water sector covering the period 2007–2025 along

with a five year plan for the period 2007–2012. Parallel to

that, a strategy for urban and rural wastewater was prepared

while an organization analysis was also conducted for the

water and wastewater sectors.

All of these strategies have been preceded by diagnostic

analyses of the national water and wastewater position,

forming the basis for action plans that aim, among other

goals, to reduce per capita consumption; increase supply

coverage and reliability; reduce leakage and increase waste-

water treatment capacity. Other measures include phasing

out of coastal wells to stop seawater intrusion; maximizing

the GMR supply for regions near the main lines; introducing

desalination for coastal areas when the GMR option becomes

too expensive; and ensuring adequate back-up through

keeping wells in reserve and increasing storage capacity.

Detailed plans for institutional reforms to strengthen the role

of government institutions and public utility companies have

also been presented.

However, the instability of institutional structures and the

lack of qualified human resources have impeded the imple-

mentation of most action plans and programmes. Moreover,

the political and economic conditions that prevailed during

and after the embargoes and sanctions imposed on Libya in

the 1980s and 1990s, and the fall in oil prices during the

same period, have led to serious budget cuts.

Starting in 2011, the country has undergone a period

of political and economic instability that has led to the

suspension of most development projects. This phase and

its implications may extend for several years to come.

Libya has invested heavily in achieving a robust and

efficient water supply and sanitation system, but has been

unable to sustain the gradual growth of this sector due to

the low technical capacity and the political and economic

instability over the past four decades. Nevertheless, Libya is

potentially capable of meeting SDG 6, provided that it soon

regains stability, and to achieve this, there will be an urgent

need to quickly mobilize large investments to implement new

water and sanitation projects and renovate existing ones.

In the years to come, development priorities will certainly

change, and the country may therefore lag behind, especially

with respect to wastewater treatment and reuse.

Sources of domestic water supply

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

2005

2010

2015

Local groundwater

GMR

Desalination

%

Source: GWA