[

] 32

A B

et ter

W

or ld

supply capacity is limited, toilet flushing in some house-

holds in a village may compete with the basic drinking water

needs of others. Improved waterless toilet options therefore

need to be seriously considered where water supply capacity

and financial resources are limited. Use of flushing toilets

increases village water supply needs by 20–30%, and creates

a blackwater waste stream with high potential health risks.

Provision of adequate treatment facilities to manage

these sustainably is relatively costly for Fijian villagers and

requires competent and experienced technicians, engineers

and tradespeople who are able to effectively engage with

villagers, and are suitably remunerated for their work. These

skills are frequently unavailable in rural areas, and villagers

are reluctant to pay for such services. An appropriate policy

and regulatory framework is also necessary to promote

uptake of appropriate technical solutions and ensure they

are properly implemented.

Sustainable and effective village sanitation approaches

must be tailored to the particular site and soil characteristics

of a village or dwelling, and cognisant of the needs and finan-

cial resources of communities. Factors to consider include:

• Preferences of users, although this may shift with provi-

sion of improved knowledge and experience of alternatives

• Risk of contaminating surface and groundwater resources

used for drinking, and areas where people bathe, wash,

play, fish and gather shellfish, or may otherwise be exposed

• Surrounding population density, availability of suitable

land and coordination between neighbouring households

• Strength of village leadership and governance, and capac-

ity to operate and maintain systems

• Government policies and regulations.

A key finding fromwork carried out in Fiji has been the critical

importance of participatory capacity-building, in tandemwith

technical approaches, to raise and embed the understanding

of health and sanitation issues, enable appropriate choices

to be made, and mobilise village-wide actions. These can be

important drivers for the acceptance of village responsibili-

ties, and the prioritisation and uptake of improved water and

wastewater management systems and hygienic behaviours.

Involvement of women, who tend to take primary responsi-

bility for the health of their families, was especially important

for promoting action across the whole WASH spectrum.

Making visible the unseen

Water-borne gastro-intestinal diarrhoeal illnesses and secondary

infection of cuts, grazes and skin lesions, for example from scabies

and insect bites, are common health problems in Fijian villages.

Because of the hot, high-humidity climate, Fijian villagers, especially

the children, swim and bathe frequently in streams and lagoons

around villages. Communal bathing and clothes washing are often

also important social events in daily village life, and water from

these sources may also be used for drinking and cooking during

periods when piped or roof water supplies are unavailable.

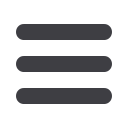

Simple low-cost water quality testing was used alongside a variety

of other participatory activities to help assess water-borne health

risks in and around villages. With the involvement of women and

members of water and health committees, relevant surface and

drinking water quality sampling sites were identified, sampled, and

microbiologically assessed using simplified faecal indicator testing

methods – H2S paper strips, 3M Petrifilm™ or HyServe Compact Dry™

E.coli plate counts – and a field incubator. Feedback of results to the

village the next day, after 24 hours incubation, showed significant

faecal contamination of bathing areas and some surface water

source around the villages. This could be traced back to discharges of

blackwater from flushing toilets, and kitchen and bathroom greywater,

without appropriate treatment and disposal systems or necessary

maintenance. Small village pig enclosures also proved to be

significant sources of faecal contamination. Such cross-contamination

has the potential to substantially increase people’s exposure to faecal

microbes and related health and environmental risks.

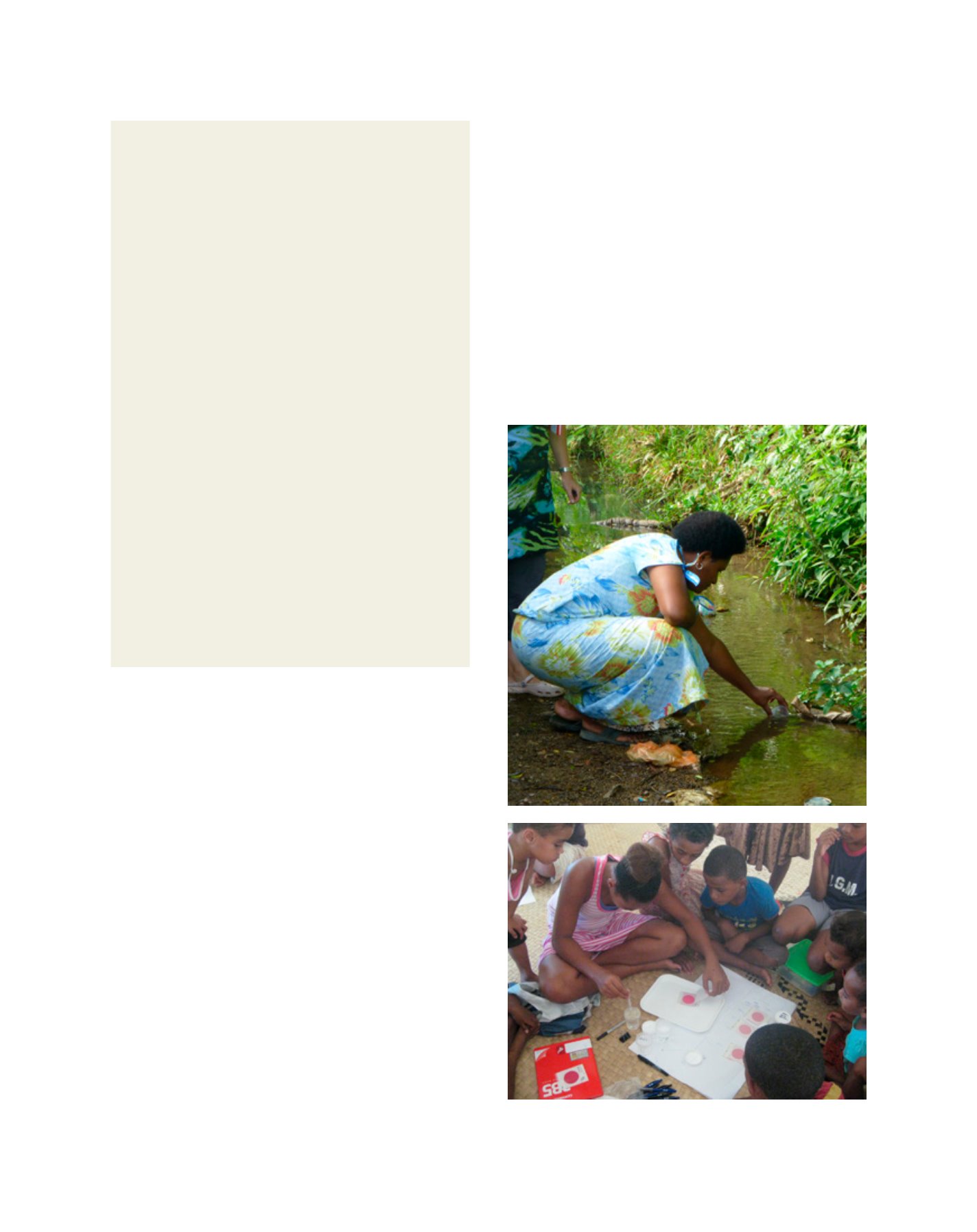

Making visible the, otherwise unseen, microbiological state of

waters within and around the village has increased understanding of

wastewater sources and transmission pathways, and the potential

health risks of different drinking water sources and bathing areas

within villages. Direct visual assessment of the density of coloured

blotches formed by growing E. coli bacterial colonies on the plates

appeared to be more readily understood by villagers – and more

influential – than showing numbers on a graph. This helped build a real

world understanding of the links between water, sanitation and health.

Involvement of villagers in site selection, sampling of water resources and

testing the faecal microbiological status of those waters

Image: C.Tanner, NIWA

Image: C.Tanner, NIWA