[

] 87

A B

et ter

W

or ld

A thorough stakeholder assessment of the sub-catchments

related to the proposed Ntabelanga Dam – the first proposed

dam of the two – was conducted in 2016.

2

The results from

the assessment and the ongoing research clearly showed

the complexity of the governance and land use within the

catchments. These complexities are a challenge, but with

a larger investment in communication, and dedicated staff

within the catchment dealing with community engagement,

these complexities are better understood and planned for.

Despite the presence of various government departments in

the catchment, natural resource-related decision making is

mainly controlled by individual farmers – with advice and

support from their agricultural suppliers – and traditional

authorities – chiefs, headmen and sub-headmen.

Planned restoration work will be done through the govern-

ment’s poverty alleviation mechanism, the Expanded Public

Works Programme and implemented by DEA NRM. These

restoration operations will potentially create 558 real jobs

in the green economy per year. This should equate to R450

million injected into the local economies of the catchments.

The restoration work in conjunction with the sustainable

land use management implicit in the Ntabelanga Lalini

Ecological Infrastructure Project goals can be seen as an

insurance policy for all the South African governments’

investment in infrastructure in the catchment.

The standard approaches to ecological restoration deals

directly with the problem and not the cause of the problem.

Gully head erosion in wetlands is stopped with engineering

interventions in most instances, but the driver of the degra-

dation is generally not dealt with. NLEIP aims to identify

the drivers and implement the required change to reduce the

land degradation whilst dealing with the identified problems

within the priority ecosystems.

The management of invasive alien plants is being done

differently in these catchments. The standard approach

works from the top of the catchment down to the bottom.

The NLEIP has investigated which species are being used by

local communities and which sites the communities would

like to have remain intact. The invasive species are primarily

used for firewood and building materials. A comprehensive

plan is being developed to allow invasive woodlots while

clearing the remainder of the invasive plants.

The injudicious use of fire in the catchment needs to be

addressed thorough fire management plans that are devel-

oped with the land users and the communities living within

the catchment.

The restoration of wetlands, grasslands and forests is

carried out in a manner that supports local business develop-

ment. The restoration material, plants, grasses and tree seeds

are harvested within the catchment and grown by the local

communities. The plants and trees are then bought from

them for the restoration work, which they in turn plant and

take responsibility for, thus creating a chain of ownership

and responsibility. Baseline monitoring of restoration efforts

in the catchment is done by trained community members

instead of using universities and specialists.

The socio-ecological model for these catchments is centred

on people and their livelihoods. This project aims to build

intervention measures for improved ecosystems functional-

ity that will, in turn, allow greater access to water and for a

longer period of time.

This initiative has thus tried in a bold and ambitious way,

to view its challenge through a social-ecological lens – one

which considers both social and biophysical domains jointly,

not with physical on one side and social on the other. Apart

from the participatory emphasis being promoted across the

many appropriate levels of resource use and governance, the

culture that the project is striving to engender is also explicitly

reflexive, using feedback and learning principles from strate-

gic adaptive management and developmental evaluation

3

.

Given the task at hand, and the particular history of the

catchment, the situation described in this article has taken

several years to start realising in this aspirational form.

With this longer start-up investment as a basis, the Natural

Resource Management Programmes organisation hopes to

trial in practice what has long been envisioned – navigating

through the complex reality in a manner which takes cogni-

sance of that complexity. This realisation is in its early stages

and there are no illusions about the multiple challenges, but

it is hoped that it will create a more appropriate approach

towards sustainability.

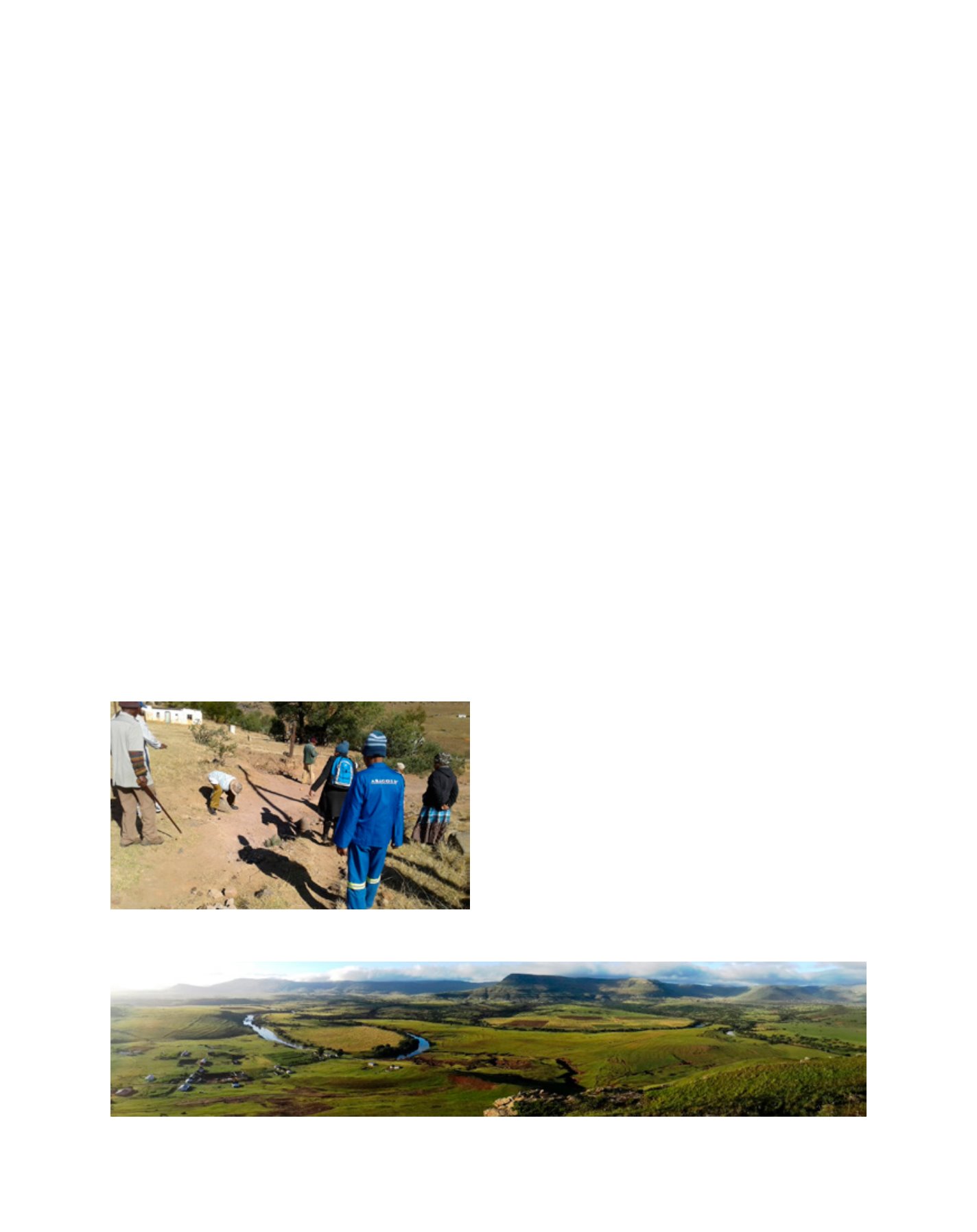

Sunrise over Shukunxa Village in the NLEIP catchment

A typical large erosion feature that has reached bedrock and is now steadily

progressing laterally and removing valuable topsoil

Image: Dylan Weyer

Image: DEA RSA